With powerful hardware working together with an industry-leading camera system and intuitive AI experiences, everyday tasks have never been easier and faster

I’m SO into this, right now

Not a Review: Immersive games. If you read Andre’s review of FEAR 3 then you know that we think it’s a great game. It has tight and unexpectedly varied gameplay, pretty good graphics and an all-encompassing sense of immersion. That last bit is the most important part of a good game, because if a game immerses you, if it can get you involved in its… vibe (I suppose is the right word), then it’s a lot easier to overlook whatever flaws it may have.

And make no mistake, FEAR 3 had its fair share of flaws. A slightly unusual control scheme for one and gameplay tailored for co-op, but that didn’t make allowances for a solo playthrough during certain setpieces. There were a few other things, but ultimately they don’t matter because the developers succeeded where they needed to the most, by getting me immersed in the world.

Getting that sense of immersion right is probably the hardest part of creating a game. When it works, even the most pedestrian of games can become enjoyable. I believe this game is the ultimate example of good immersion.

How good COULD it be?

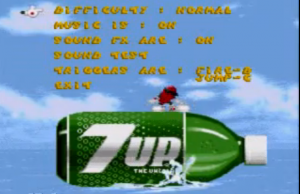

Cool Spot is probably the best corporate sponsored videogame ever, and starred 7-Up cool drink’s mascot from the ‘90s, the eponymous Cool Spot. A large part of the game’s success lay at the feet of the character Cool Spot being, well, cool. Programmed by legendary game designer David Perry (before his rise to prominence with Disney’s Aladdin and Earthworm Jim), Cool Spot was a derivative side-scrolling platformer typical of the early ‘90s. Cool Spot moved from left to right, collected non-sentient spots – because in a ‘90s  platformer game you had to collect something – and then rescued a fellow Cool Spot from a cage. There was no narrative, no visual gimmick, no special moves, no challenging enemies, no innovative features, no iconic boss battles. Left to right. Rescue buddy. Move to next level. End.

platformer game you had to collect something – and then rescued a fellow Cool Spot from a cage. There was no narrative, no visual gimmick, no special moves, no challenging enemies, no innovative features, no iconic boss battles. Left to right. Rescue buddy. Move to next level. End.

On the face of it, it seems ridiculous to compare FEAR 3 with Cool Spot. The games couldn’t be more different. Cool Spot is whimsical, nostalgia candy, while FEAR 3 is horror, blood and slow-mo headshots. But they both succeed, because their key feature is that they draw you into their world. Somehow, they were immersive.

Granted, Cool Spot hasn’t aged well, clearly because it was never a very good game to begin with, and the Cool Spot character was a very ‘90s phenomenon. But at that time, that game was the shit. That cartridge spent days in my Sega Megadrive, never to be removed, all because Cool Spot was so damned immersive. The combination of great graphics, sweet music and Cool Spot’s insouciant swagger generated a sense of cool in all who played it. It really was a case of style winning over substance, in the best way possible. In fact, I got so caught up in Cool Spot, that all I drank in 1994 was 7-Up.

Granted, Cool Spot hasn’t aged well, clearly because it was never a very good game to begin with, and the Cool Spot character was a very ‘90s phenomenon. But at that time, that game was the shit. That cartridge spent days in my Sega Megadrive, never to be removed, all because Cool Spot was so damned immersive. The combination of great graphics, sweet music and Cool Spot’s insouciant swagger generated a sense of cool in all who played it. It really was a case of style winning over substance, in the best way possible. In fact, I got so caught up in Cool Spot, that all I drank in 1994 was 7-Up.

Pinning it down

The consensus on what exactly immersion in gameplay is hard to pin down, but Canadian game designer and author, François-Dominic Laramee, gets close. He says it’s a game’s ability “…to create suspension of disbelief, a state in which the player’s mind forgets that it is being subjected to entertainment and instead accepts what it perceives as reality.” That is a widely held view on what games ultimately need to strive for to be immersive. This view may be true, but it is also wrong.

There is nothing wrong with creating a fiction that is so wholly realised that it dominates a player’s perceived reality, but it is most certainly not the only way to do it. Consider games like Tetris, Farmville or Angry Birds. There is never a point in those experiences where the player develops suspension of disbelief, yet they do experience immersion. The game has engrossed them in some fashion, but that doesn’t mean they’ve lost sight of the fact that they are playing a game.

Immersion is a confluence of factors not always intentionally brought together: the right music, the right aesthetic design, the right controls, and more. Notice I didn’t say good music or good controls. Because sometimes immersion can come about from errors or unexpected design quirks.

Take Street Fighter II. People played SFII because it made them feel like real bad-asses. The key feature in that game was the ability to combo your attacks into each other, which meant you could sometimes put a surprisingly huge hurting on an opponent. That was not intentional on the part of the developers. It was a bug that SFII producer Noritaka Funamizu left in the game because he figured it was too difficult for a player to intentionally pull off to make it a useful feature. Legions of SFII fans disagree. Nowadays, a solid combo system is a priority in all one-on-one fighting games; in fact, it’s core in most games that have a melee combat component. Leaving that bug was the “right controls” for SFII and it ensured that the game immersed its players in a world of competitive martial arts.

Take Street Fighter II. People played SFII because it made them feel like real bad-asses. The key feature in that game was the ability to combo your attacks into each other, which meant you could sometimes put a surprisingly huge hurting on an opponent. That was not intentional on the part of the developers. It was a bug that SFII producer Noritaka Funamizu left in the game because he figured it was too difficult for a player to intentionally pull off to make it a useful feature. Legions of SFII fans disagree. Nowadays, a solid combo system is a priority in all one-on-one fighting games; in fact, it’s core in most games that have a melee combat component. Leaving that bug was the “right controls” for SFII and it ensured that the game immersed its players in a world of competitive martial arts.

You can’t plan to have it

The downside is that you can’t program for immersion. No amount of technology or money can guarantee it. Consider the Move and Kinect, two devices that were supposed to guarantee a higher level of immersion. Both excellent technically, yet neither device has had that breakout hit yet. Nothing coming from them yet has been totally immersive.

Immersion is that X-factor. That extra something that just lets one game feel better than the next game. It’s that something that gets you in to the game. It’s that intangible something that makes everything work.

And you either have it or you don’t.