MTN South Africa has once again emerged as the country’s top-performing mobile network, securing the highest score in the Q2 2025 MyBroadband Network Quality…

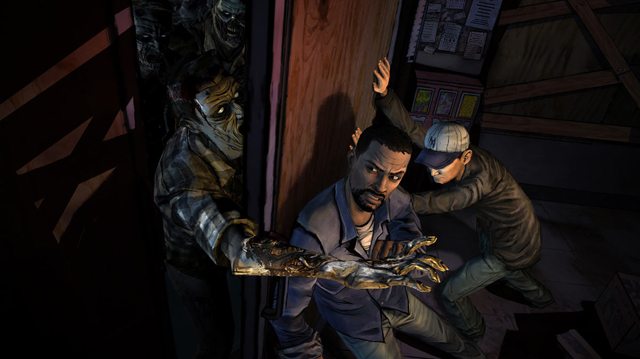

Choose your own zombie adventure in The Walking Dead

Telltale Games’ The Walking Dead (TWD) is a lot less game, a lot more interactive story. Like a great Choose Your Own Adventure novel, your decisions mould the way the story plays out. The choices you make here are both challenging and mature.

Zombie-Tropes

Based on Robert Kirkman’s award-winning comic book series, Telltale’s The Walking Dead has some serious work to do to find relevance in the zombie-saturated media world that we live in. We’re running on zombie-overload, desensitised to stories of the undead that munch on their living counterparts, are completely inept at opening doors and get mowed down by small groups of survivors regularly.

Zombies are the least of the clichés in the zombie genre though, it’s the survivors and the ways they are presented again and again that is exhausting. How many times will one policeman join up with a man with a mysterious past (prison or army) who happens to be really great with a gun… but can he trust him with one? Add to that duo either a young family or pregnant woman and a few assholes of which one will redeem himself and you’ve got yourself a neat little zombie movie/book/comic/TV show.

Telltale’s attempt is not completely cliché free either. You play as Lee Everett, a man with a mysterious past (convicted felon in this case), who has to join up with various survivors to endure the big ol’ Z-apocalypse. The game doesn’t centre on the mowing down of the undead ala Left 4 Dead or Dead Island, but rather focuses on the ‘people-skills’ required to deal with strangers when confronted with constant danger. To say that TWD is a middle-management simulation set in the apocalypse would do it an injustice, but I imagine the skills might cross over.

It’s decision-time

What makes TWD stand out as a piece of zombie media is having decision-making at the heart of its mechanics. The choices are tough, often sitting in a morally grey area, and have to be made quickly. Every dialogue prompt gives you three to four options and a few seconds to choose your response. It takes a little getting used to, but keeps you on your feet, giving the game a sense of tension.

Early decisions revolve around how much you reveal about Lee’s history as a convicted murderer. Choosing sides during an argument drastically changes how people perceive you, and you’ll constantly feel your relationships developing according to how you play the social game. Balancing group dynamics is a challenge from a game-perspective, but also from a moral one. The way you play Lee might very well reveal something about yourself, and for a game to have you question morality is a testament to its adult mood and content.

There is a spanner in the works though; early on Lee meets Clementine, an eight-year-old girl, most likely orphaned post zombie breakout. Lee promises to take care of her in her parents’ absence and looking after Clementine is the driving force behind a lot of Lee’s decisions. There is always a choice for you to put her first (or last) when faced with touch choices. Again, how you play the game might indicate what kind of parent you might be now or in the future – no pressure.

Decision-making is not limited to dialogue alone and action is often required. For example you might have to ration out the food or show mercy to an infected before they fully turn. But at its most intense TWD asks you to make life-or-death choices. These moments are strangely emotional because the strong writing and characters make you actually care about the ‘people’ that you are saving, or leaving to the hungry undead. This compassion is further enhanced by top-notch voice acting, especially from Lee and Clementine.

TWD made me feel something games rarely do – remorse – for killing (or rather not saving) a fellow human. In a medium in which killing is glorified and built into its very mechanics (for most genres), it’s quite refreshing to play a game that has you questioning life and death rather than playing it out.

Besides the choice-mechanic there isn’t a whole lot to do game-wise: environmental interaction is limited and there are almost no puzzles (sorry adventure fans). Luckily the dialogue and characters are highly engrossing and a few sparse, yet intense, quick-time events spice things up.

The storyline has been fantastic; chapter two, especially, proves that during the apocalypse, the zombies are the least of your worries when humans are around. You’ll almost certainly play through each chapter’s two to three hours in one sitting each, and with three more of the five-chapter season to come, there’s a lot more story on the horizon.

Engineer your story

The game makes strong use of cel-shaded graphics made popular by Borderlands and the Dragonball Z games. The look compliments the TWD canon by perfectly contrasting the black-and-white comic book upon which it is based, and also gives the game a distinct feel.

Telltale’s engine is starting to wear though. Graphically there is touch of jerkiness here and there, but TWD is definitely their best looking game to date. There is an odd audio glitch that sees a character’s voice become really soft for one line every now and then but these are slight blemishes on what is otherwise a great experience.

I can’t endorse TWD as a game: its limited interaction, minimal puzzles and few technical hiccups prevent that. But I can highly recommend it as an interactive story – one that focuses on plot, character and atmosphere.

Like Heavy Rain, TWD blurs the lines between games and movies. This is an interactive story, a well told one, and if more games centre their mechanics on tough and interesting choices around morality and human relationships, then that’s a great thing, zombies or not.

Version Tested: PC

Also available on Mac, PS3, XBOX 360, iPhone/iPad