With powerful hardware working together with an industry-leading camera system and intuitive AI experiences, everyday tasks have never been easier and faster

Black Mesa: Half-Life reborn

Gabe Newell must be smiling. He is a man who has always placed community before commerce. Having made his millions at Microsoft he left to found Valve Software, a company that would make games without compromise. His Half-Life series prioritized quality over time constraints and financial concessions. The series protagonist, like Newell, truly was a free man. Indeed Newell is conceivably videogaming’s auteur — a creative soul who has no patience for publishing houses that assume dogmatic rule. And he is also egalitarian, seemingly without ego. Valve openly allows novices and upstarts to tinker and modify its existing games and broadcast the results via its digital distribution platform, Steam. Whether the modifications are serious or jovial, the choice is yours. It’s the Valve way.

And never before has a modification arrived that is so deep, so immense. In Black Mesa, Newell and Valve have realised its motto of affording talented, unassuming people the chance to produce the truly extraordinary. Black Mesa is a complete recreation of the original Half-Life, rendered in Valve’s up-to-date Source engine. The developer’s intentions are clear: to make Half-Life 1 as beautiful as its sequel, and then some. Much like Valve’s own games, it’s been repeatedly delayed, yet eight years on it’s here when we need it most. This might not be Half-Life 3, not by a stretch, but it’s a timely reminder of why we bought into the series in the first place, and why we clamour for the concluding chapter in Gordon Freeman’s saga.

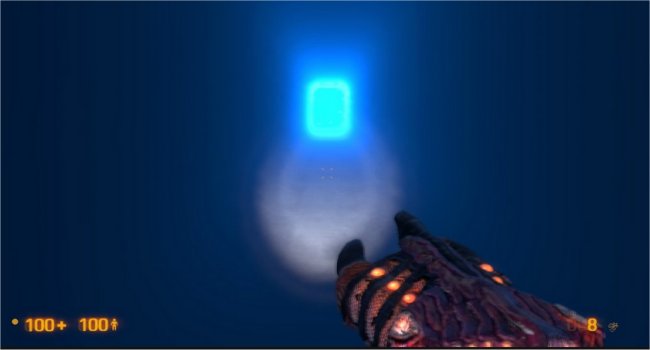

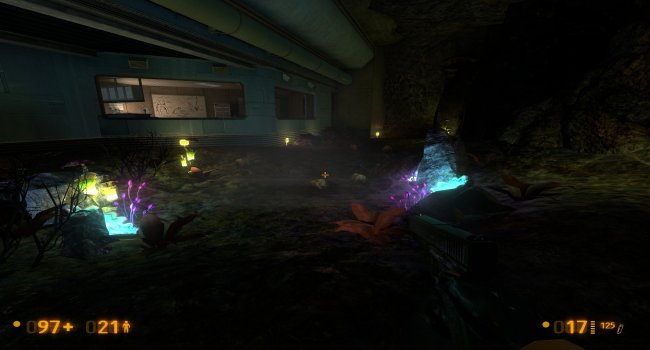

It’s a remarkably polished and considered remake, the product of men and women who love the series. Nothing has been unnecessarily altered. The original introductory sequence for instance, a five-minute ride on a monorail, remains intact, yet it now highlights the new visuals. Harnessing the power of the Source engine, Black Mesa overhauls the textures, implements realistic physics and replaces all existing character models with new faces and bodies. As you familiarise yourself with the game’s controls aboard the monorail you’ll notice subtle motion blur as you swing the camera around, while “Bloom” feathers the lightning for a subtler look. This is ostensibly the same game: only now it makes use of your quad-core PC.

That’s not to say parts of the game have not been altered or expanded upon. Certain levels are more intricate owing to the introduction of physics. You might find that a crucial lever is detatched from its socket. It needs to be picked up and replaced in its rightful place while headcrabs besiege you. Devoid of the gravity gun the physics engine is never a major part of the game, but it does make the world feel more organic, and were it missing, Black Mesa would suffer for it. Elsewhere, the corridored interiors of the research facility are bigger, and various outdoor areas have been widened in scope. What’s more, you’ll rarely spy the same character twice. That ubiquitous security guard now comes in various forms and guises. Some are balding, some are white, some are black. And yes, Eli Vance resembles the Eli Vance of Half-Life 2.

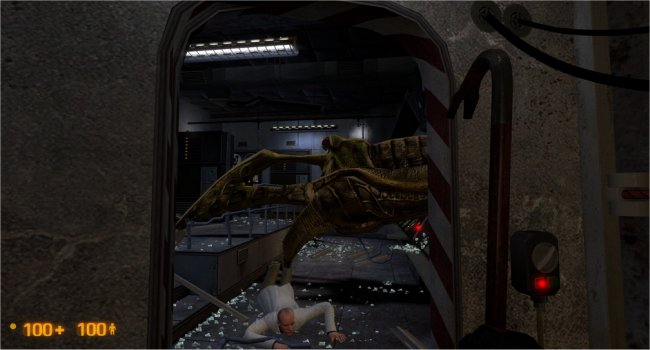

No amount of polishing can shroud the fact that the Black Mesa Research Facility simply isn’t as interesting as Half-Life 2’s City 17. There’s none of the Orwellian intrigue, or the dystopic menace. On the other hand, more than ever, Half-Life 1 strikes me as a black comedy. When I first played the game I was too young to notice the self-referential humour, the verbose scientific language. In particular, Valve clearly enjoys sending scientists to their death.

Whether it’s falling from a ledge or being vacuumed through a ventilation shaft by a tentacled alien, their misfortune is frequent comic relief. Then the military step in, and as one scientist informs me, they’re saved. Off-screen, I hear him proffering his ID to the soldiers. The next instant, gunshots pepper the air. They are they bumbling reminder this is only a game, not real life. Perhaps it is indicative of society pre-9/11. Today we hanker, manically and masochistically, for films and games that are grimly realistic. Even Half-Life 2 is far more oppressive. Thank God Black Mesa reclaims comedy with such aplomb.

Should you wish to play this gem (and you should) you’ll need Steam and the Source SDK Base (2007) installed. Both are free, as is the game itself, which can be downloaded from the official website, release.blackmesasource.com. And in truth, this isn’t really a review. Why would anyone be averse to a game that is free? It guarantees you ten hours of nostalgic fun, dressed up in an all-new look. While Black Mesa ends before Xen (the developers are looking to re-work this section in conjunction with the physics engine) it’s impossible to ignore what a commodity Black Mesa is: an example of the merits of independent development versus the commercial machine. Valve has long championed the idea that quality is an artistic endeavour, not a monetary one. Just don’t expect it to always arrive on time.