South Africa’s creators, coders and founders are under pressure to do more with less. Whether you’re running a meme page from Mitchells Plain, debugging…

Zimbabwe, Mozambique and South Africa’s EV battery future

Zimbabwe and Mozambique have an abundance of materials required for building automotive grade EV batteries. But where are they going to be made?

The IRA Act and EU incentives have driven tremendous demand for EVs in America and Europe, triggering enhanced demand for rare earth metals and material sourcing in some of the world’s remote and volatile locations.

Mineral and metal supply chains are being reevaluated for their demand integrity as refiners and battery cell manufacturers attempt to secure material. Chinese battery manufacturers are the kingmakers, controlling more than two-thirds of global battery output.

With its geographical diversity and resource depth, Africa has immense mineral supply potential to supply global battery material needs, although hyperlocalised conflicts and logistics infrastructure remain issues. Although battery chemistries are evolving, lithium remains an essential base material, and Zimbabwe has some of the world’s largest resources.

American and European sanctions have impacted Zimbabwe’s development trajectory, but its lithium resources are proving to be a vital source of income, circumventing American or European influence. Chinese companies dominate the global market for large, energy-dense batteries, and Zimbabwe has increasingly become a preferred source of lithium for Chinese suppliers.

Making materials into money

Are lithium demand for electric vehicle power units and energy storage the state revenue hedge Zimbabwe desperately needs? The Zimbabwean government has limited access to international capital markets and is attempting to leverage its lithium resources with beneficiation requirements to rejuvenate sectors of the domestic economy.

Despite the richness of resources in most African countries, precious little economic development transpires beyond primary extraction. A lack of stable industrial-scale electric supply to rural areas, fabrication skills and tooling support has prevented mineral and metals beneficiation from developing near African mines.

As Chinese lithium resource extraction scales in Zimbabwe, material transport volumes will test infrastructure. Zimbabwe’s landlocked geography is a disadvantage that its neighbours have exploited.

During the 1980s, at the height of the intra-state conflict in Southern Africa, the vulnerability of Zimbabwe’s dependence on neighbouring ports was ruthlessly exploited by the South African government, with regular sabotage of the crucial Beira railway line, forcing Zimbabwean exports through South Africa – with an implied monopoly of cost.

The best and most logical export route for Zimbabwean lithium to China is by rail via the port of Beira. This is an established trade corridor capable of handling bulk tonnages at high frequencies.

Although Beira is exposed to East African cyclone season, divided into two datelines (Mat-June and October-November), its port has modernised and is functional. Significant investment in Maputo’s large port has dramatically enhanced its capabilities and offers another secure transhipment option for suppliers needing to ship Zimbabwean lithium eastwards.

Risks and graphite realities in Mozambique

Mozambique’s political stakeholding reflects its decolonial dynamics, with the liberation political movement, FRELIMO, having been in power since 1975. Its only opposition is RENAMO, which controlled the Mozambiquan interior, close to the Zimbabwean border, for much of the last quarter of the 20th century.

FRELIMO and RENAMO operate in acrimony, remaining true to their traditional power bases, either inland or coastal.

RENAMO’s origin story is clouded by its close relationship with and support from the Rhodesian security forces during the late 1970s. Most road and rail shipments from Zimbabwe to Mozambiquan ports route through traditional RENAMO inland areas, and opportunistic friction tax is not to be discounted.

Mozambique contains valuable pure graphite resources, but the latest graphite mining project is located in the country’s far northern Cabo Delgado province, the site of a bitter insurgency which has driven oil and gas investors to abandon many projects.

The SADC EV opportunity

Although Zimbabwean lithium and Mozambiquan graphite are currently structured and supplied as separate products, there is a significant opportunity for regional beneficiation driven by EV assembly.

The SADC community’s most industrialised economy, South Africa, has a highly developed and sophisticated automotive industry. Most vehicles built in South Africa are for luxury brands and exported to America and the EU. To sustain its lucrative automotive industry, South Africa must ensure that its vehicle production adapts to regulations and trends shaping demand in its destination markets, implying a future production portfolio of battery-powered EVs.

African governments, like Zimbabwe and Mozambique, can leverage their resource status to establish regional beneficiation, with South Africa finally signalling some intent to incentivise and support localised EV production, primarily for export, with a recent policy white paper.

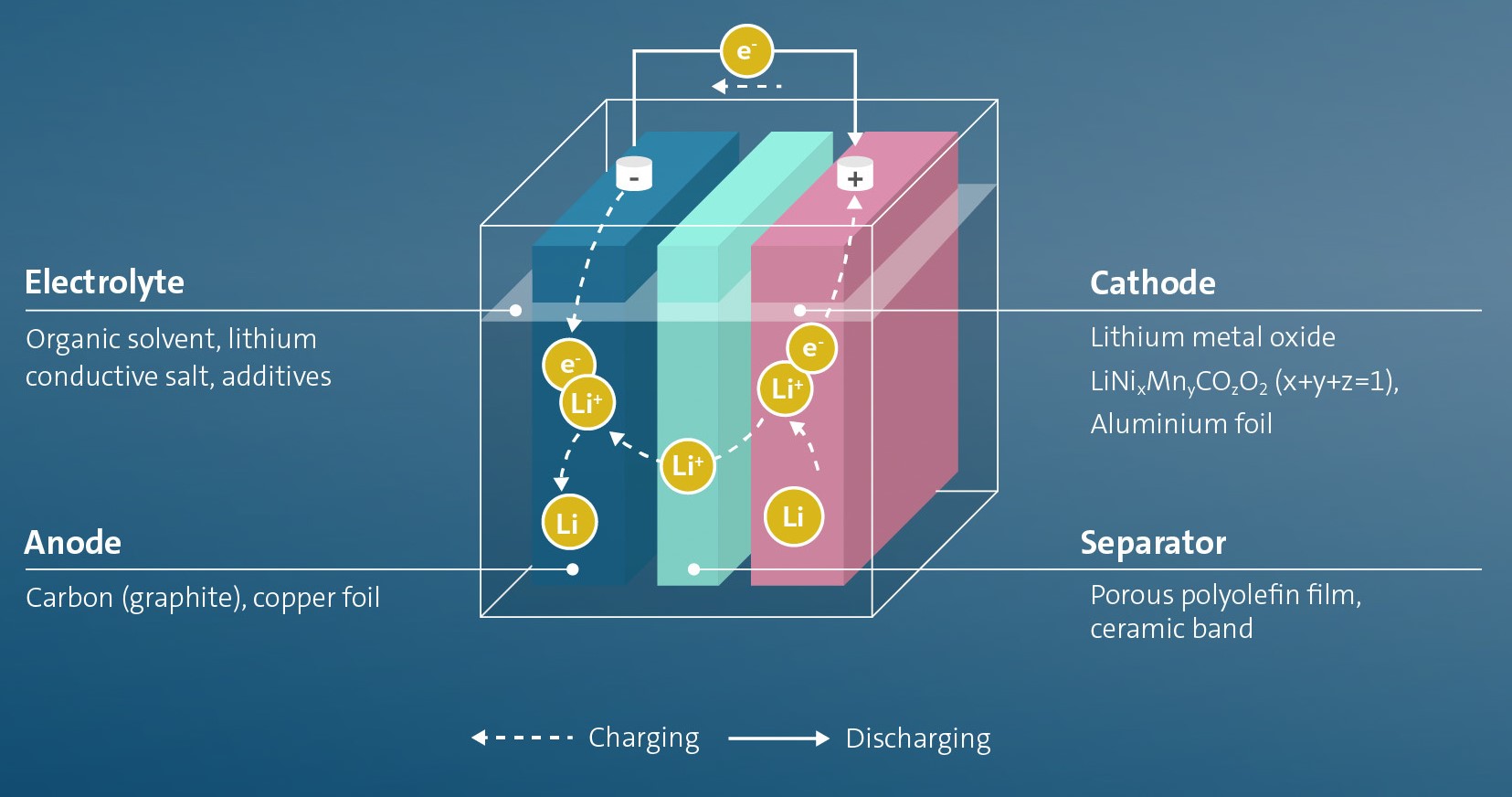

A decisive development outcome could be battery source material mined in Zimbabwe and Mozambique, being shipped to refining and assembly specialists in South Africa. But which entity is going to shape those source materials into automotive-grade batteries?

Afrivolt wishes to establish a domestic gigafactory to serve the South African lithium-ion needs. However, its site of preference is the Atlantis Special Economic Zone, outside Cape Town, which problematically isn’t near any of the legacy auto assembly assets, clustered in the Eastern Cape, Gauteng and Durban. The initial capacity for Afrivolt’s gigafactory is rated at 1.5 GWh, with a peak capacity of 5 GWh.

An African EV story is emerging

As demand for rare earth metals increases, African source locations with reasonable access to established transport infrastructure will become progressively valuable.

The likelihood of African rare earth metal sources being diminished by new mining exploration and extraction assets in North America or Europe is negligible. The population density and environmental regulations in most American States and European countries make rare metal extraction nearly impossible or prohibitively expensive.

Local communities must be appeased for primary mining companies or downstream battery manufacturers to access stable source material and unhindered transhipment. And that will be challenging, as rare earth metals and lithium mining are rarely as labour-intensive as traditional gold, copper or diamond extraction. Fewer on-site mining job opportunities could be a difficult sell to local communities, although an innovative energy security exchange could offset the frustration of marginal opportunities.

Providing battery energy storage and electrification to parts of rural Mozambique without stable power, could be the expedient strategy for those companies wanting to secure their extraction security for some of the world’s most viable lithium and graphite resources.

On-site beneficiation will remain challenging. But an interlinked and scaled SADC effort, with Zimbabwean and Mozambiquan battery source materials and South African manufacturing skills provided by six global brands with established vehicle assembly facilities in Gauteng and the Eastern Cape, would be a transformative outcome.

A significant question is whether regional rail networks will harmonise or create logistical friction, something that South African mining and automotive assembly companies have been dealing with for the last year.

For the vision of a sub-Saharan EV industry, Zimbabwean lithium and Mozambiquan graphite need to travel south for beneficiation. Instead of being shipped east.