South Africa’s online dating scene is shifting in 2026 as users move away from endless swiping toward niche apps focused on values, safety, and real connection.

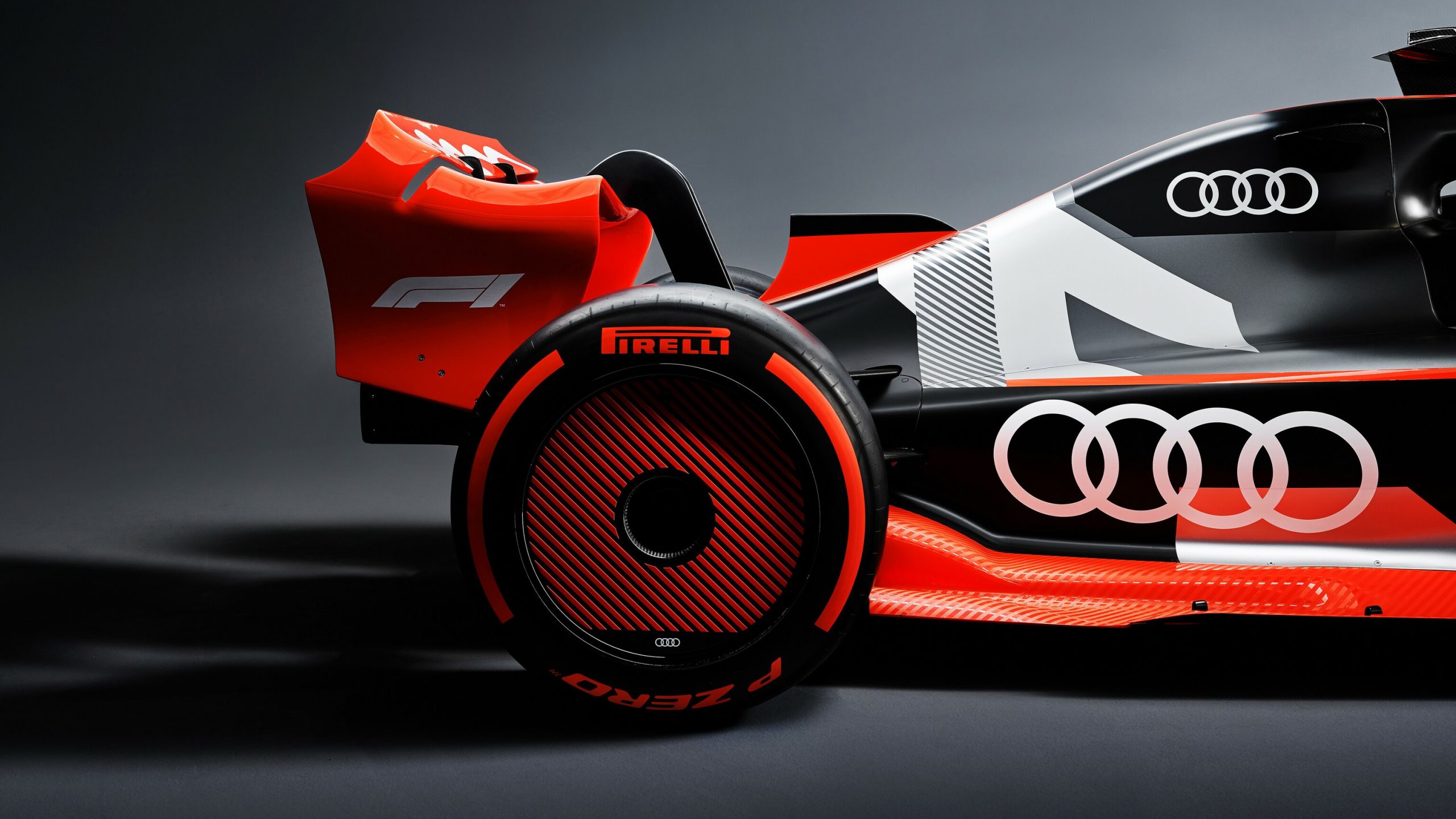

The F1 risk for Audi

Car companies and F1. There’s no average outcome – either you win or suffer brand depreciation.

The allure of is obvious. The glamour, technical innovation, and global reach make F1 very appealing for car companies to invest in. But the technical complexity, often unrelatable trajectory of innovation (how do winglets benefit road cars?), and risk of becoming backmarkers are real.

Ferrari has been the most continuous presence and even when the Scuderia team fares poorly, it hardly influences Ferrari’s road car business.

The glamour and high-performance association between Ferrari’s race team and its road car business are a natural symmetry. However, for most other car companies, who produce diverse models of many sizes and configurations at more affordable prices, the FIA’s premium formula is risky. Very.

It requires an enormous amount of money to succeed. The artificial narrowing of budgets and R&D, under the cost cap, has mediated that – but it remains telling how influential money is to success. But also, paradoxically, how huge budgets don’t guarantee victory in F1.

Going beyond Le Mans

Since the mid-2010s, Mercedes-Benz has been a dominant force in F1, but it spent an extraordinary amount of money to make that happen. By contrast, Toyota left F1 after only a few years without any race wins. When car companies are ranked by available cash and resources, Toyota usually ranks first, marking its inability to convert cash and resources into winning notable.

Where car companies have been most successful in top-tier FIA racing, is providing engines instead of running complete teams. As powertrain suppliers, Renault and Honda have a huge tally of Grand Prix wins. So does Ford, although the American brand failed spectacularly when it attempted a sub-branded team in the guise of Jaguar. BMW? From the turbo to V10 era, it enjoyed great success as an engine supplier – never risking the complexity of creating its own team.

This raises questions regarding Audi’s F1 entry with a team, instead of as a powertrain supplier. The risk is massive.

Audi is a premium brand with an established reputation for technical innovation. It also has a storied history of winning at Le Mans, the motorsport event, arguably providing more real-world relatability for car owners and brand durability. Le Mans cars have doors, wipers and headlights – all features Grand Prix racing cars don’t.

An Italian boss

Audi’s wildly ambitious F1 campaign is off to a troubled start. The rationale for it isn’t impossible to understand: F1 engines are hybridized, and Audi’s road car business is pursuing an EV-future. F1 also has a more global and digitally interconnected audience now than ever in its history.

However, all the German technical acumen and resources don’t guarantee good outcomes in the realm of F1, where rules are often ambiguously interpreted. And technical secrets, closely guarded. In a shock announcement this week, Audi has purged its F1 team of its two German leaders – CEO Andreas Seidl and Chairman of the Board of Directors Oliver Hoffmann.

Replacing both Seidl and Hoffman is vastly experienced former Ferrari team director, Mattia Binotto. The Italian engineer has nearly three decades of F1 experience, but his challenges at Audi are immense. He needs to consolidate two roles into one and evolve the currently uncompetitive Sauber cars, into Audi podium contenders by 2026.

F1 and the road car issue

The scheduled 2026 rule changes, creating much smaller cars, will reduce some of the legacy technical benefits that F1’s dominant teams currently enjoy. It creates an opportunity for Sauber’s renewal as an innovative Audi.

F1 failure has unintended consequences for car companies. Jaguar’s awful spell in F1 started a long decline for its road car business. Honda’s exit became Brawn’s triumph, which eventually created the dominant Mercedes Grand Prix team of Lewis Hamilton’s many championships.

Perhaps most tellingly is the memory of Toyota’s Grand Prix racing campaign. The Japanese company might have failed in its F1 objectives, but its F1 investment arguably created Lexus’s FLA’s greatest front-engined driver’s car of all time.

Could Audi’s F1 adventure inspire a new generation of Audi high-performance road cars, even if Binotto doesn’t bring the wins?